On Saturday, I failed to perform in Jena. Am I devastated? No! But I’m absolutely disappointed and a little embarrassed (although whatever, my process is my process). I threw well in Rome. I threw well in Halle. I had an overall great trip to Europe for three weeks! But finishing it off that way leaves a bad taste in my mouth, and motivation to understand my own brain and failures moving forward in this long season. I want to share two big reasons why I fail. These aren’t specific to Jena: I do the same technical things wrong consistently, and I let self-doubt creep in after being alone for a while.

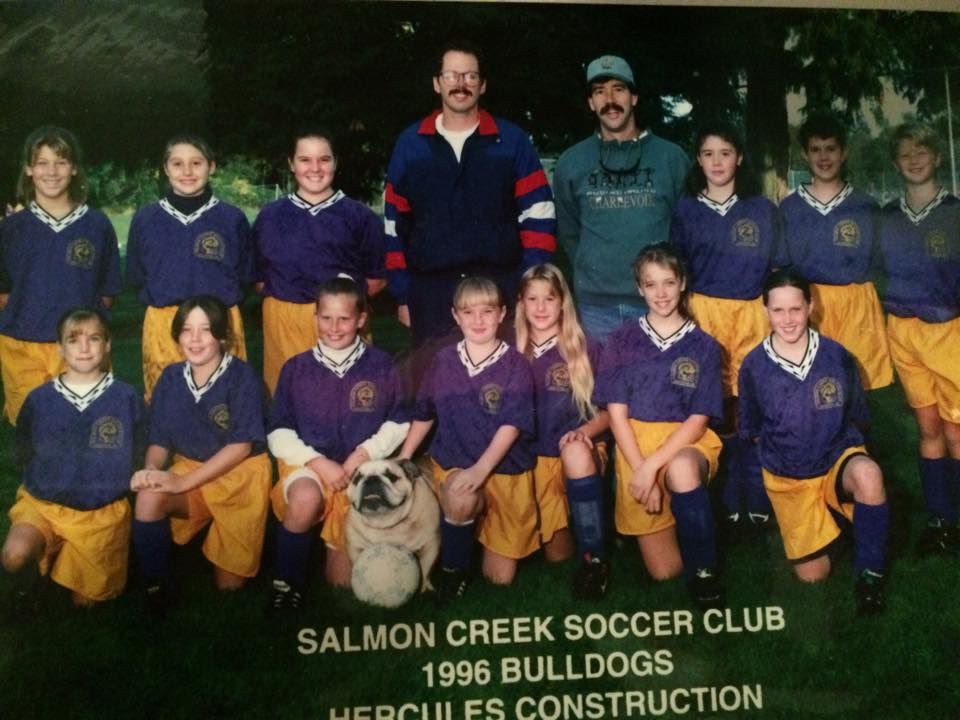

Ich liebe Hallesche Werfertage!

Trusting myself has always seemed normal to me. I blame good parenting! I know I put the work in. I know I have what it takes. I know that I care the most about the outcome (team situations were frustrating for me and I’ve been let down by people). But when I have any little dent in my independence armor and there’s someone there to lean on, I leeeeaaaan.

It’s my problem, not those willing and helpful peoples’ issue. I need better blinders, and to trust my own instincts, not necessarily in competition (I’m good at that), but when things don’t go as planned surrounding it. Long travel day? Go to the pool instead. Only bus later than I hope to go to the meet? Roll with it and shorten the warm-up when I know I’ll have a warm place to do so (prioritize the throwing stuff). Extra worried about my body throwing twice within 3 days? Strengthen the mind with visualization rather than just ignoring the negativity. And do all the mobility and core rather than just resting and hoping to feel better! I’ve always been good at following instructions. I’m coachable! And I highly value Jamie’s input into my training and competition preparation plan. But I also know he’s open to my feedback. For whatever reason, when I don’t feel good but know I have a meet coming up, I put my head down and stick stubbornly to the plan rather than expressing what I know, 99% of the time, we’ll both agree with. I should have gone to the pool on Friday after leaving the Rome hotel at 7:30am and arriving in Jena at 5:30pm, sweating all day. I could have done some core in my room first, then swam some laps, sprinted a little, and relaxed, weightless. I didn’t. Dummy.

There’s this saying that the hay is in the barn. Have you ever been around a farm? Animals need more than hay. My Mom’s horses get a carefully concocted mixture of hay, fancy hay, beet pulp, grains, various vitamins, and of course, love. The hay may be in the barn before big competitions (whatever “big” means to you: Every meet can feel big at this level), but you still need grains to finish the job. To do it right. I’ve ignored that instinct one too many times, and I’m finally processing it. Before Zurich and after Rovereto last year, I was finally brave enough to focus fully on what I wanted, and harvest the grain of mental fortitude and specific mobility and stability in those last days and moments. To do things I know make me feel invincible in this post-ACL, different-for-me era. I can be more successful. I just also have to be braver in looking my big, scary goals in the face and taking care of the details that can get me there.

My technical mistakes are always the same. They present themselves as “losing the tip” or “forward,” which in Jena’s left head/crosswind was a disaster. But actually it all starts for me with my right foot. And really my left foot. I spent 8 years solidifying a habit of striking backward with my right leg after my impulse, which I could get away with because of the gift of shoulder mobility. I look forward to lumbar arthritis as a result of hyperextension of that area for close to a decade as well (and more since I’m still not 100% disciplined). Anyway, with tiredness and some soreness (I’m very good at managing stiffness/being dinged up in one area, but 2/3/4 gets harder) comes timidity and lazy legs. Even though I know my legs were the reasons for 62.08m in Halle and 63.11m in Rome, I willed them to go and they just wouldn’t!

On Saturday, I let people (who are not Dana) tell me what to do. I already know what to do, and what they told me would have been accomplished by my strategy (specifically steps 2 and 3), but I allowed myself to be distracted by input.

I need to:

1. Gradually accelerate down the runway.

2. Hit a strong impulse after already using my left leg as a driver in crossovers.

3. Be patient in my tunnel of power (knee up/toe up and left arm closed), wait for the ground with my right foot.

4. Drive my right knee to the ground immediately upon right foot contact while keeping left arm closed.

5. Keep the handle of the javelin “hidden” from the sector right behind my head.

6. Be a freaking tree in my left leg.

7. Push my chest forward after all of that happens.

8. Watch the jav soooooar.

Everything happens if I hit an impulse and actually wait for the ground. But when I allow myself to be distracted, I focus on the end result rather than the key step that will lead to that result. In a headwind, that’s “keep the tip down,” “control the tip,” and “tip by your eye.” When I think about that cue, my only focus becomes keeping my chest up, which gets me tall in my legs and forward, not allowing good, powerful leg action. Inactive legs mean no impulse, and the body’s rush to create speed with a pawing right foot and pressure behind me rather than under me, forcing me forward more. A pushy right means I don’t have to snap a solid block down, because I feel support from a leg (the right). The left arm swings open for balance and because there’s time, and the right arm follows suit by swinging around. I try to maintain connection with the implement by extending/breaking my wrist, both skyrocketing the javelin and not applying energy to it.

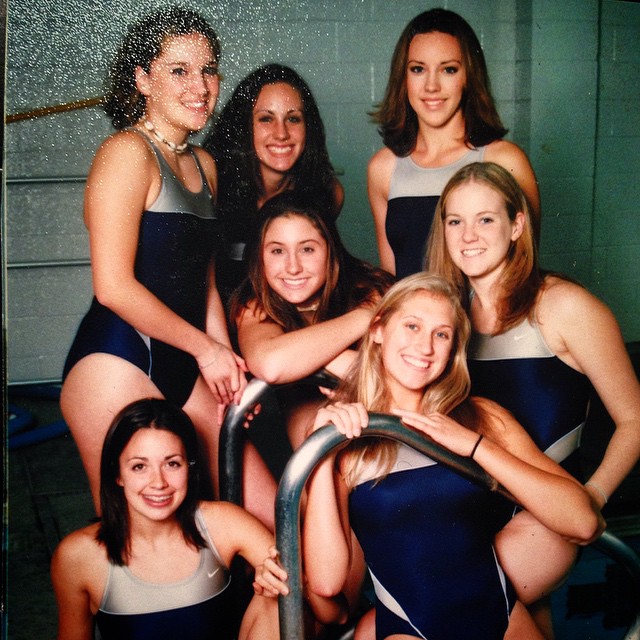

My face sometimes.

It’s tough to break the self-doubt cycle in the midst of a competition, especially when you have excuses (four travel days and three meets in a week, end of 6-week trip, two days after the most intensity my body has felt in throwing in months, headwind, etc.). But I’m sick of it. Details are important and empowering. Let them be by allowing yourself to pay attention to them. Trust yourself, even when you’re tired, by practicing mental toughness, however you harness it. Change your cycle. Be better!